Archiving stories of women buying from Pheriwalas (Pedlars in India)

About :

This archive was initiated through my MA Final projects’ research where I recorded oral history from a sample of nine women who reside in different corners of the country. They all shared experiences of buying textiles coming from a different state in India through a pedlar coming to their doorstep and selling these items. They eventually became a part of the family and regularly visit these houses, for some since 20-25 years.

Context :

In an unorganised market system, such as a bazaar in India, local sellers directly interact with multiple consumers. In the 1960s, these consumers were often women, as they were taking care of household chores while men would work outside. Historians have bypassed the study of tete-a-tete trader and consumer relationship in such an economic structure. India being a patchwork of multiple cultures, the movement of textile crafts from one state to another remains an under-explored subject in the discussions of Indian textile history.

Acknowledging the fragmentary scholarly attention given to this topic in the past, this research alludes to the significance of small trading structures within the subcontinent - ‘the Indian pedlar trade’. Further, it references a number of disciplines such as anthropology, trading history, sociology, textile material culture, sari and south Asian textiles, family archives, biographies through textiles, museum studies and collecting dress in India. The dynamic study investigates with the help of oral testimonies and memories on how Indian textiles with their geographical relevance, traditions, and narratives were circulated across the peninsular country and acquired meaning in the emergence of the twentieth-century consumer economy.

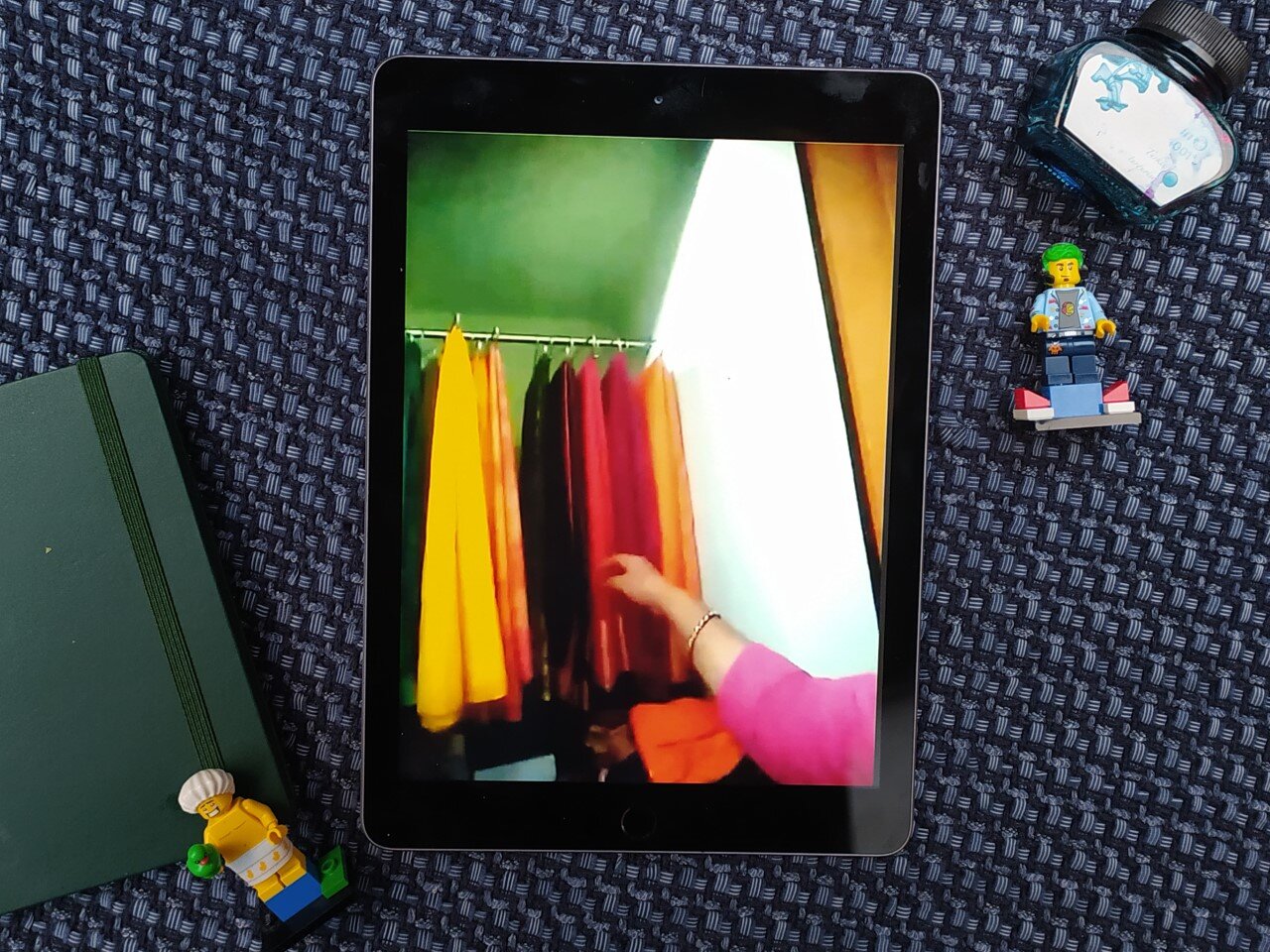

Clippings from oral testimonies collected during the research focussing on pedlar-trade of Textile Crafts within India and its impact on the lives of women collecting personal wardrobes in the late 20th century - present.

Translation:

00:00 - “There used to be a huge bundle, a bag and a cloth tote, in which they used to carry everything”

00:18 - “ I asked him- how old are you? , He said, 20 years, So I asked why was he not studying. To which he replied that he can’t pursue studies because of financial reasons”

00:28 - “ ‘Dada! Auro shaari dekha’ We say like this in Bengali, meaning ‘Show me more saris that you brought’, or ‘ Dada, fir kab ayenge, Dada?’ meaning ‘Elder Brother, when will you come next, elder brother ?’ They used to call my mother and my aunties Didi meaning sister”

00:48 - “Kashmiris used to also come, and if they wanted to have some snacks and drinks, we would offer them”

00:57 - “During the festival of Sakranti, my husband used to bet on chicken/cockfights and win a sum. This money he would later give it to me and my sisters to buy new saris from pheriwalas”

01:30 - “We used to ask him, ‘if the length of the sari is above 5 meters, or we wouldn’t buy it. At that time the trend was to wear a longer pallu (sari’s open end), so we used to ask him if the sari was 5 and a half meters or more, if not, we wouldn’t buy it. But this particular Dhakai sari was only 5 meters, I loved it so much and it was the last piece he had, so I attached another half a meter on the inside end of the sari after buying it”

01:55 - “He used to bring some nuts & berries from Kashmir for my daughters as a gift, he would call himself as my brother - uncle of my children”

02:10 - “ We used to buy from them, but my father didn’t like it [giggles]. So we used to sit in the verandah downstairs to buy from the pheriwalas and get money from upstairs [sneakily] because if Father gets back and finds out, he’d nag.”

02:35 - “His father used to come to my mother-in-law’s house, but his father then passed away so no one came by after that, and after many years I met him, Aatik Bhai, at my friend’s place. Then when I showed interest in buying shawls, he came to my house and I purchased a green jaal (all over embroidered) shawl, I still remember”

Shaped and embodied by interactions and experiences, everyday textiles become primal in rendering these closely akin memories.

‘In such textile tales we sense the extraordinary in the ordinary, yet in daily life, the significance of the quotidian is overshadowed by habit and sometimes only revealed when what has been taken for granted is lost.’ (Goett, 2009).

Threaded with the delicacy of family-like relationships, the poignant memory of a familiar stranger carrying textiles from workshop to one’s home, such (extra)ordinary traditions have been losing their existence and in essence, making their way to this archive- acknowledged.